The phrase “pleading the Fifth” has been popularized in television shows and movies and is not simply a Hollywood invention. It’s a specific privilege against self-incrimination that is mentioned in the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Under certain circumstances, witnesses can invoke their Fifth Amendment privilege to prevent potential self-incrimination. An example of this would be during a grand jury proceeding where witnesses who are called to testify might believe they their testimony could incriminate them in other cases. Due to this provision, they can refuse to testify. In a criminal trial defendants can refuse to take the witness stand.

Miranda v. Arizona

A courtroom isn’t necessary for applying Fifth Amendment privilege. In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Miranda v. Arizona, that an individual in police custody must be warned of their Miranda rights prior to questioning. This case is one of the most famous in American history and created well-known language many rely on if facing arrest.

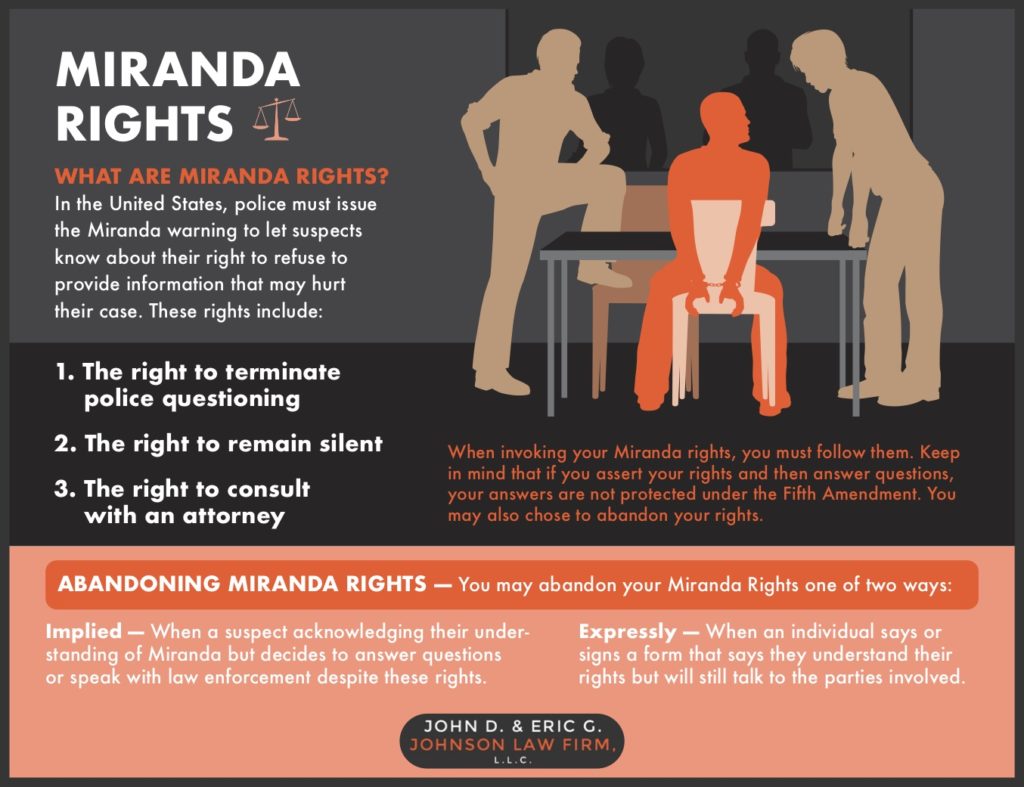

In Miranda v. Arizona, the court found that an individual needs to clearly know their rights against self-incrimination at the time of arrest. Since this ruling, law enforcement must issue a Miranda warning which states one has the following rights:

“The right to remain silent, that anything he says can be used against him a court of law, that he has the right to the presence of an attorney, and that if he cannot afford an attorney one will be appointed for him prior to any questioning if he so desires.”

Though officers aren’t required to recite this language word for word, they are required to get the meaning of this statement across without any confusion to their suspects.

Limitations of Miranda Warnings

Miranda warnings are required in specific situations. If an officer suspects someone of a crime or when arresting someone, a warning isn’t always necessary. If an officer violates the Miranda rights of an individual or fails to recite them, it won’t be considered a cause for dismissal of the case. Illegally gotten statements by law enforcement are still admissible in court for certain purposes. A prosecutor cannot prove their case against a defendant with these type of statements, but only use them to discredit testimony.

Two situations must occur for officers to be required to issue the Miranda Warning:

- Take suspects into custody or significantly withholding their freedom, and

- Interrogate them

If an individual isn’t in custody or prevented from leaving, a warning isn’t necessary. It is possible officers can forgo the warning when arresting someone but have to hold off on interrogation.

It’s important to understand the meaning of interrogation when understanding one’s Fifth Amendment rights. Miranda refers to questions directed at the arrested individual that would elicit an incriminating answer. If police stop an individual on suspicion of drunk driving and an officer asks how much they have had to drink, an answer to this could be very damaging for the suspect.

How to Invoke Your Miranda Rights

Once notified of their Miranda Rights, the suspect may invoke them at any point. A suspect advised of the Miranda rights is allowed at any point to assert them and stop any questioning before it even begins. One could also decide to answers some questions if they wish before this happens, but anything said prior to asserting their rights can be used in court by the prosecution.

As mentioned before, two key situations must be met for an officer to advise someone of their Fifth Amendment rights under Miranda v. Arizona. Once this warning has been given, the suspect can invoke their right to remain silent and stop questioning until having the opportunity to speak with a lawyer.

These two rights have specific functions in protecting against self-incrimination.

- The right to stop questioning until the suspect consults with an attorney, and possibly has them present when this process resumes

- The right to remain silent and say nothing

These two rights have very different effects and circumstances when being invoked. If a defendant or suspect uses their right to counsel under Miranda, law enforcement usually has to hold off on any interrogation until the accused retains a lawyer. Of course, if a suspect engages in further communication with the authorities, then an interrogation can proceed. If claiming the right to remain silent, law enforcement has more flexibility when pursuing another round of questioning.

Miranda Rights are not Black and White

Sometimes those accused of crimes might waive their Miranda rights altogether, but determining the validity of that action might be difficult. Waiving these rights must be done purposefully and without pressure placed on the suspect. Additionally, the consequences and rights of forgoing them must be clear to the party waiving these rights.

There are a couple of ways to go about abandoning Miranda Rights.

Expressly – This is when an individual says or signs a form that says they understand their rights but will talk to the parties involved anyway.

Implied – This involves a suspect acknowledging their understanding of Miranda but decides to answer questions or speak with law enforcement despite these rights.

When invoking Miranda rights, the suspect must be absolutely clear of their intent to use and follow them. If you assert your right to silence, and then you answer questions, the answers you give are not protected under the Fifth Amendment.

Hire a Criminal Defense Lawyer to Protect Your Rights

If arrested, and law enforcement gives you a Miranda warning, it is best to follow that advice by remaining silent and requesting an attorney. An experienced criminal defense attorney will be able to help you not make any incriminating statements and walk you through a potential police interview.

Eric G. Johnson of The Law Offices of John D. & Eric G. Johnson has many years of experience defending criminal cases throughout Louisiana while protecting the rights of the accused. Eric has handled a diverse range of cases involving violent offenses to white collar crimes. Let Eric advise you of the best next steps in your case. Contact us today at (318) 377-1555 for a free case evaluation or complete our contact form.